Prospective Courses

As a graduate student at the University of Kentucky, I have been the primary instructor for a variety of entry level courses for English majors and a number of different writing courses. However, I have not yet had the opportunity to teach major-level courses in my home discipline. What follows are a variety of prospective courses that might appeal to English Literature Majors with an interest in Shakespeare, the Renaissance, and the early modern stage.

The Evolution of the British Subject:

English Literature Survey, 900-1688

While covering centuries of historical and artistic development, the typical British Literature survey course offers an array of representative (and often iconic) works in a blur of pedagogical momentum. This course, designed to expose majors to the canon of British fiction, can be hard for many students to wrap their heads around. Instead of focusing entirely on the canon. my prospective survey would build from a thematic core to anchor its investigation of significant literature from its earliest beginnings through the end of the seventeenth century, covering the Old English, Middle English, and Early Modern literary periods. That unifying theme: What does it mean to be a British subject?

Throughout this prospective course, students would explore how early British literature defined (and rewrote) the social obligations that unite individuals and help form a larger community. Through this, we will trace the growth of personal agency and the emergence of diverse voices that would, eventually, give birth to the Enlightenment and the Modern Era.

While the people of Anglo-Saxon Brittania would have thought little of the term "personal agency," works like Beowulf and the Second Shepherd's Play explored the necessity of a unified community and the individual’s role in its preservation. But as civil societies evolved throughout the Medieval period, authors like Geoffrey Chaucer, Thomas Hoccleve, and Margery Kempe pushed against the restrictions of this social order and crafted stories that explored the personal idiosyncrasies that could empower or constrain an individual. This move to a self-fashioned identity would come to define the great literature of the Renaissance, inspiring the work of William Shakespeare, John Milton, and countless others, and would embolden the subjects of Caroline England to reshape the society in which they lived. While considering the progression of these ideas from the campfires of our Nordic ancestors to the broadsheets of the early republic, the class would attempt to define for itself what it meant to be a British subject at the dawn of the modern era.

Of His Age, and For All Time:

Shakespearean Resonances

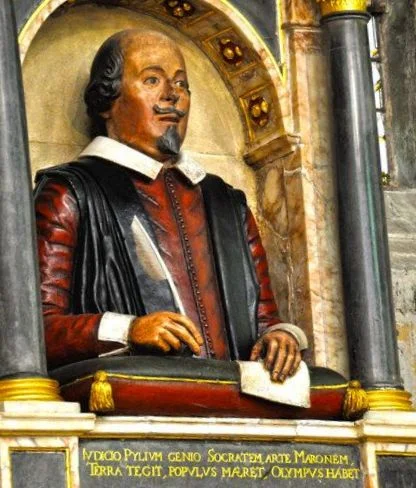

True to Jonson’s eulogistic praise in the First Folio, William Shakespeare is considered the canonical voice for one of the most influential periods in Anglo-American history, but this popular perspective often obscures the literary influences and contemporary resonances that shaped this literary cliché. This prospective course would re-contextualize the typical Shakespearean survey by placing these signature pieces in a network of plays and texts that move beyond the confines of the Globe. This course would move beyond the reputation and see how the plays resonated throughout history to shape our current understanding of Shakespeare.

Looking at dramatic and non-dramatic literature from Renaissance London, this course would investigate a central theme of Shakespeare’s oeuvre and compare his interpretation with contemporaries before tracing its evolution in later adaptations of the canonical original. For instance, Shakespeare’s comedies often highlight opinionated women (Kate, Hermione, Viola, etc.) that violate social conventions before, ultimately, being confined by marital bonds, but the challenge that these plays offer to generic convention is better understood when these plays are shown in context. Read next to raucous city comedies like The Roaring Girl or as adaptations of more conservative prose works like Pandosto, a more nuanced view of Shakespearean heroines emerges – one that compliments the riot grrrl energy of 10 Things I Hate About You much more than the decorous adaptation of Trevor Nunn’s Twelfth Night.

While this is more than enough material to delve into for a full semester, this course design would be adaptable to a number of different thematic cores. Variations on this course could focus on political ambition (Macbeth, the Henriad, Tamburlaine, etc.), the importance of social credit (Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, Bartholomew Fair, etc.), and more. Regardless of the theme, this course would take three to four works from the Shakespearean canon and trace how a central theme was developed across the author’s lifetime and how these often-isolated plays circulated within a broader conversation and evolved with our modern public debates. This course would trace how Shakespeare came to reflect his time and forever change literary history.

Ripped from the Headlines:

Renaissance Domestic Drama

These days, you will regularly find a True Crime story at the top of the New York Times Bestsellers, serialized in a Top Ten podcast, or dramatized in a gripping television drama, but the current fascination with suspenseful tales of justice ripped from the headlines is not new. In fact, the early modern London stage regularly presented material that came directly from the criminal underworld of the Renaissance to enthralled audiences of all types. This prospective seminar would investigate the domestic dramas, history plays and city comedies that drew on the news of the day to drive ticket sales and frame political statements. While doing this, we would investigate the non-canonical playwrights that made their name in this ephemeral subject matter and investigate the precarious position that this genre put both Shakespeare and Marlowe in.

The course would start with an examination of the playful criminality of Dekker and Middleton’s Roaring Girl – a play that, according to rumor, featured the titular Mary Firth, a real-life cross-dressing petty criminal, delivering the play’s defiant epilogue. This city comedy would be positioned against the cony-catching pamphlets of Robert Greene and others in order to provide context about how crime was defined in the literature of the period. The “underworld” of London was a popular carnivalesque atmosphere in which Elizabethan and Jacobean writers found the critical space from which to challenge the society in which they found themselves. And this is nowhere more evident than Middleton’s Chaste Maid in Cheapside – a burlesque of inappropriate behavior that puts the proto-capitalist marketplace of early modern England in stark contrast.

Moving from the street-level criminality of Jacobean city comedy, we would explore the sensational stories that defined the domestic sphere in the period. The selfish pursuits that motivated Alice to murder her virtuous husband in Arden of Faversham set a template for the nascent domestic drama of the period, one that drew on the morality play tradition and upheld the merchant class as paragons of contemporary culture. But this didactic approach was not universal. Thomas Heywood’s more sympathetic treatment of A Woman Killed with Kindness reshaped the genre to weigh the competing motives involved in one of the most compelling domestic stories of the Renaissance. These two plays, when considered next to the conduct books and sensational broadsides from which they drew, would offer the class a new perspective on the deep roots of true crime narratives, on the treatment of women in the period, and on the merging of criminal guilt and social shame in the early modern city.

The final unit of this course would look at the Renaissance treatment of political “crime” through two historical tragedies that touched directly on the news of the day. Marlowe’s Massacre at Paris, his last play, offers a clear picture of the artistic and commercial risk assumed when depicting a political event that was still resonant in the Elizabethan public sphere. The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of French Huguenots was seen as both a religious atrocity and a source of domestic strife by many of the Londoners in Marlowe’s audience even twenty years later. As a result, the play was not well received. On the other hand, Shakespeare’s Richard II, a play about a weak king’s inability to reign in a contentious court, was lauded and, in fact, famously commissioned for the queen 10 years after it premiered. However, this later performance occurred on the eve of the Earl of Essex’s attempted coup d’état. Despite the historical distance of Richard II’s usurpation, the play was politically potent in the waning days of the Queen’s reign and, as a result, jeopardized the future of the Globe and its most famous playwright. These historical plays would allow us to consider the impact of political censorship and the line that was carefully drawn between the escapism of true crime and the threat of political commentary.

While the plays at the center of this course may not resonate as widely as Hamlet or Doctor Faustus, they impacted had a significant influence on the success of Renaissance drama and helped shape its historical resonance for years to come. The seminar’s focus on the ephemeral nature of these specific genres would also allow students to gain a greater appreciation for the historical milieu that shaped Shakespeare and to trace the methods by which literature reacts to social events and recontextualize it for a broader audience.

Remixes and Hot Takes:

An Applied Critical Theory Course

Aristotle, Marx, Freud, Foucault, Said, Butler, etc. The big names in critical theory present a daunting task for any undergraduate that is compelled to grapple with them, as the work of these pivotal critics endeavored to decipher the cultural milieu out of which art develops. But any student that wants a better appreciation for what literature does needs to develop a deeper understanding of the aesthetics, mimetic drives, and overall theory upon which critical literacy and the English Major are based. So how can these abstract ideas be made relatable and purposeful for the uninitiated? Make them personal.

As a typical requirement for established majors, any Critical Theory course should draw on the canon of British and American Literature that students have already read (once or thrice), complicating their initial interpretation of classic literature with new theoretical perspectives. This course would ask students to take one of their favorite canonical texts (from a curated list that reflects the major works highlighted in departmental prerequisites or selected specifically for the class) and approach it with fresh eyes – multiple times throughout the semester. After gaining a clearer understanding of Romanticism, New Criticism, or Post-Colonial thought, students will use a new theoretical lens to reshape their understanding of these time-worn classics. These evolving interpretations will be honed through in-class discussion, critical essays, and evaluative debates with classmates about the incisiveness of the analysis offered by each major school of thought. By investing in a single chosen text and defending their take on it, students should leave the course with a clear understanding of how to apply each major critical lens to the prose, poetry, and, hopefully, culture beyond the timeworn classics at the heart of the course.

As an example, a student in the course may chose to focus on Hamlet as her central text for the course. While she works gain a greater appreciation for the nuances of a psychoanalytic reading of the titular character, she would also be asked to consider the difficulties of “self-fashioning” in the Tudor Court or the empowering constraints placed on the play by Aristotelian definitions of “tragedy.” And, while it might be difficult to read post-colonial theories into Hamlet, Fortinbras’s peripheral motivations might offer compelling insight on the domestic drama at the center of Shakespeare’s work. Even as this student grappled with the theory and its application, she would join her classmates in analyzing smaller pieces like Wyatt’s “Whoso List to Hunt”, Hemmingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River”, Rossetti’s “Goblin Market”, and Kureishi’s “My Son the Fanatic.” At the end of the semester, this proto-Hamlet scholar would be able to determine which theoretical lens revolutionized their original understanding of the text and argue for the continued relevancy of this canonical work in a long-form analytical essay.